Saxophone Embouchure

Embouchure means (very basically) what you do with the front part of your mouth (lips and teeth) in order to play the saxophone. It has nothing to do with the word embrasure, which is a hole in a thick wall with a window or door set back into it. However many people make that mistake.

There are several different types of embouchure

There is more than one “correct” saxophone embouchure. These three images are from an old but still very relevant book by Ben Davis (published by Henri Selmer no less) which is now sadly out of print.

The picture shows three types of embouchure:

- Fig. 5 – an embouchure in which the lower lip does not cover over the lower teeth

- Fig. 6 – the bottom lip is drawn in over the teeth and forms a cushion between the lower teeth and the reed

- Fig. 7 – the top lip also forms a cushion between the top teeth and the top of the mouthpiece. Known as the “double lip embouchure” and has been used by some greats including Lee Allen and John Coltrane

Ben Davis is of the opinion that of these three only number 5 is correct. He calls this the “new ” embouchure.” I disagree in that I don’t think any of these are wrong. They each suit different saxophone players and styles.

I originally used the embouchure in Fig. 6, but was later taught to use the lower lip without any support from the teeth. This takes a while to get used to as you need to build up the lip muscles, but I find it more flexible than the other two.

Below are some extracts from his book, which must have been quite controversial at the time, as the no-lip over teeth saxophone embouchure was quite revolutionary.

Quoted extract from The Saxophone by Ben Davis:

There are three types of embouchure, two of which, in my opinion, are wrong. I will explain what they are and why I think they are wrong as we go along.

First, the right embouchure, which I call, for the sake of differentiation, the “new” embouchure. Open the mouth in the shape of a small o; keep the lips close to, but not drawn in over the teeth. Then insert the mouthpiece. Rest the lower lip against the lower teeth; then lower the reed onto the rim of the lip, so that the inside of the lip forms a cushion between the teeth and the lip. Do not draw the lip in over the teeth. It must just rest against them so that only the thinnest part of the fleshy inside lip is pushed over the teeth when the mouthpiece is in playing position. The rest of the lower lip will then form a sort of support for that part of the reed which is immediately outside the mouth.

Next, lower the upper teeth on to the mouthpiece with the lightest of pressure. The upper lip must not come between the teeth and the mouthpiece in any way. Finally close the lips round the sides of the mouthpiece so that no air can escape from the sides of the mouth. Don’t, however, exert so much pressure that the corners of the mouth are tensed. Neither pout the lips. You have now the “new” saxophone embouchure. It is illustrated, slightly exaggerated in order to make it clearer, in Fig. 5 above.

The old saxophone embouchure (fig 6) differs in that the lower lip is drawn in over the teeth, making a thick and heavy pad of flesh for the reed to rest on. This is extremely tiring to the lip and the embouchure soon weakens, with consequent lack of control over the reed and resultant poorness of tone and harsh low notes.

Embouchure Exercises away from the Saxophone

Sometimes you are unable to practice with your instrument, but you can still work on your embouchure. Although people generally have good cotrol over their mouth and lip musicles when carrying out normal everyday activities such as eating and speaking, there are some very subtly muscle requirements necessary for gaining and maintaining good saxophone sound and flexibility. Here are a couple of things to try:

Smile/Whistle Exercise

This involves exactly what it says. You alternate quickly between a smile and a whistle. This is great for flexibility or just warming up. Players who are required to double on other woodwinds such as flute can find this very useful when having to quickly switch between instruments, as itb helps “reset” the embouchure. Ypou can do this anywhere, especially if you don’t feel self conscious when people stare at you.

Mouthpiece Exercises

We have a whole page dedicated to these, with more in the book Taming The Saxophone Volume 1.

These are good when you are in situation that means you cannot actually play the instrument, but can play the mouthpiece. (ie the sound will not bother other people). You can do this while travelling, e.g. if you are driving and stuck in a traffic jam.

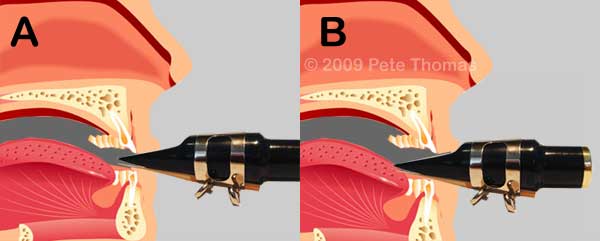

How far into your mouth should the mouthpiece be?

If you were about to put a chalk mark on the top of your mouthpiece I have to disappoint you by saying there is no one size fits all.

I have heard people say you should take in as much mouthpiece as possible, and I have heard others say you should take in as little as possible, and both of these extremes have an argument in their favour, but being extremes they are unlikely to work for anyone unless they want a very specific sound that never needs to vary much. As the saxophone is famous for being such a versatile and expressive instrument, this is an unlikely (though possible) scenario. Most players I know want to be able to play in a variety of styles, whether amateur or professional, this is really important. There are one or two superstars who have developed a personal style and stick to it, but most of us need or want to have a bit more versatility. For a working professional, the more versatile you are the more work you will get.

Each of these extremes has an advantage, but there is a trade off. Playing with a very large amount in your mouth can definitely help you very quickly get a big loud sound (although for some people it can time to get used to it). Why a big loud sound? You might think it’s because there is more reed in the mouth to vibrate. There’s no doubt about that and many players who use an embouchure like this do play very loud, either out of choice and sometimes out of necessity (if they have to compete with an amplified band). Likewise a tiny amount of mouthpiece in the mouth would appear to mean that a large part of the reed is stifled by their lips so less reed in the mouth to vibrate.

This sounds like it might make sense, but in practice it doesn’t actually work like that, maybe because the entire reed can vibrate however much it is in the mouth.

So why doesn’t everyone just play with the mouthpiece right in? Because this will sacrifice the control you get, not only from your lips, but also your tongue, and more importantly, the amount of reed that you’d think is vibrating may not equate to louder or better sound anyway. The amount of control that is sacrificed by a lot of mouthpiece taken in varies from individual to individual. The control from your lower lip (and jaw) is necessary not only for good control of effects such as vibrato and note bending, and also for the more basic function of tuning. No saxophone is 100% in tune, the more problems you have with intonation, the harder this will be to rectify if more mouthpiece is in your mouth.

Another thing to consider is that the more mouthpiece there is in your mouth, the harder it will be to get good clean articulation , as your tongue may need to be more arched than if there is less mouthpiece in the way. As I said above, none of this need be a big problem if control and versatility is not one of your aims and your tuning is so good that there is little need to vary the intonation.

You can also see that in diagram B, the lower lip has less control over the vibrations at the tip of the reed.

OK, again, exactly how far in should the mouthpiece be?

As I said above the ideal amount can vary from individual to individual. There are some variables:

- Overbite/underbite

- Tongue size

- Mouthpiece Curve

- Tone and Style

Overbite/underbite

People with a more pronounced overbite (Lisa Simpson!), would obviously need to have their top teeth further onto the biteplate, in order to achieve he same lower lip position as someone with an underbite. When observing other players’ embouchure from photos, you need to be aware of this: looks can be deceptive!

Tongue size

Tongue sizes can vary enormously, and as mentioned above on other pages and, good clean articulation is paramount for a good tone. The longer your tongue is, the harder it will be to use it it effectively with large amounts of mouthpiece.

Mouthpiece Curve

Famous instructors such as Larry Teal advise that the correct place for the lower lip is at the point where the mouthpiece facing (curve) angles away from the the reed, and although I do not necessarily agree, I think this can be a very good starting point. From this you should also be able to understand how it is impossible to give exact measurements as mouthpieces have different lengths of curve.

Tone and Style

For any jazz or rock soloist, a personal or even unique sound is often a good thing. Top players in these fields often have the luxury of not needing to play with as much versatility as a regular gigging musician or keen hobbyist, who may need to adapt between a classical style for some pit work or wind bands and a more modern jazz, pop or fusion sound for commercial gigs or recording sessions. In this case using either extreme of a lot or very little mouthpiece could be a bad thing, unless you are very adept at quickly switching between the two ends of the spectrum

One of the best teachers ever, Joe Allard, recommends a more flexible approach, which I completely agree with. In an interview, David Dempsey mentions that Joe taught that there was no one answer, you need to be able to play with more mouthpiece or less mouthpiece.

The Answer to the question

The best answer I can think of is to take in as little as possible without compromising any of the sound. For some people this may well mean playing with a lot of mouthpiece in their mouth, for others it could be just the very tip. But for most, somewhere between the two extremes. So either of these two methods might work if you start from a medium amount:

- Experiment with taking in more, but while listening to any improvements. Ideally, not just loudness, as there are other ways to achieve this. Constantly check that you still have the same control over pitch (vibrato, bending, etc.)

- Experiment with less, and listen to see if there is any deterioration in loudness. Also check to see if control over pitch is improving. If so, but you are losing volume, then this could be the way to go, but work on other methods to improve your airstream (e.g. Diaphragm Breathing).

Either way, you may find some improvement, or you may just end up where you started. But it’s worth trying both. I am sorry not to be able to give you exact measurements, but I hope I have presented plenty of food for thought to help you work out your own best embouchure.

very helpful thank you

Interesting! I’ve always done the double lip embouchure, as my teeth on the reed and mouthpiece have been uncomfortable, and I don’t like the feel of the reed or mouthpiece on my teeth. Once gotten used to, it’s very comfortable for me to play.

Is it also necessary sometimes to lower the bottom lip when moving to a different octave? Or should the embrocure never change?

IMO it’s fine to move your lip if necessary