A quick recap about chords

We learned in the book that chords are two or more notes played together. We know how chords are constructed, that they are derived from scales by counting up alternate notes:

1 – 3 – 5 – 7

We also know that chords are used for two main purposes:

Chords in the backing music

This is the music you play along to as a soloist, either with a band or pre-recorded playalong track. As you might expect, chords are played by instruments capable of playing several notes at once, e.g. guitar and/or keyboards.

Chords used in your improvising

We also learned that when improvising over the chords, we use the chords more as a framework to make the improvisation sound good and interesting. We are unable to play the actual chords on the saxophone except as arpeggios – as a series of notes. In this case we have learned that it is useful to know what the chord notes are, so that we can use them to help give our improvisation some structure and interest.

Because we can be creative, we are not constrained in any way by the order in which the notes of the chord are played. At first we can use that order (1 3 5 7) as an exercise, however in the heat of a actual solo, it is totally unnecessary to use them like that. We can make use of the chord notes in any order we like. There is nothing to stop you playing 1 3 5 7, but if you stick purely to that kind of formula, your solo will probably sound more like an exercise than an improvisation.

Voicing

What we need to grasp now is that although we have learned to think of the chords as constructed from the bottom (root) upwards, the notes do not have to be played in that order. In fact on instruments such as the guitar it is often not physically possible to do that. We use the term (chord) voicing to describe how the notes placed within the chord. (The word voicing is used because music theory is often based on choral music).

Also we need to know that the root does not always have to be at the bottom of the chord . We will look at that in the next section (Inversions) but for now we will look at chords that do have the root not at the bottom. We call this a Root Position chord.

In this case, provided that the root note is at the bottom of the chord, it really does not matter what order or what octave the other notes are in. It often doesn’t matter whether a chord instrument even plays all the notes, provided there are other instruments that are playing them. For example, the guitarist or keyboard player can often leave out the root, provided there is a bass player who can play it.

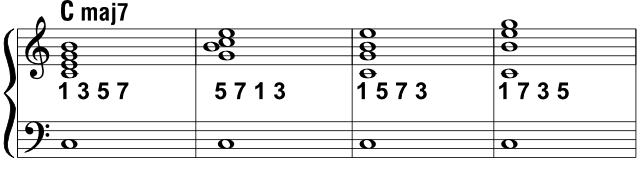

To illustrate, here are some chords of C major 7, and possible voicings:

Point of interest:

The first two examples are called close position voicing – all the notes are close together and fit within one octave. The second two are open position voicing as the notes are not consecutive chord notes, and are spread over more than one octave.

It is useful to know about this if you are interested in arranging

In this case we might assume the C in the bass clef is played by a bass instrument (or left hand of a keyboard) so these are all root position. However the voicings shown in the treble clef might be as played by a guitarist or keyboard player.

In the video example, although you cannot see it due to space on the keyboard, a root note C is being played lower down on all examples.

The numbers, as you’ve no doubt realised if you have read the book, refer to the notes and their relation to the root. It makes no difference whether they are in the same octave or one or more octaves higher. We still use the same numbers. So for example, the 3 in the first bar and the 3 in the second bar both refer to the note E. We are no longer restricted to thinking that we count up the scale from the root. Of course that is how the chord is originally derived, but this shows us how the chord can be voiced in different ways.

Inversions

An inversion describes chords that are not in root position, in other words the bass note is a chord note other than the root. In the above example, a root note was played on all the different chord voicings, so even though the voicings were different, the chords were in root position.

In this example, the chord in the treble clef is voiced 3 5 1 – It is a C triad. (As we mention above, it doesn’t matter that the 1 is not at the bottom. To show inversions as chord symbols, we use a diagonal slash under the chord symbol to show which note is in the bass.

The last chord has a B in the bass, so we chord say it is a C major 7, however this is not necessary in practice.

Again, this could represent exactly what a keyboard player might play: a chord voiced in the right hand and the bass note which defines the inversion in the left hand.

Alternatively this could represent a guitar chord (as shown in the treble clef) and a bass note as played by a bass player. So even though the guitarist is not palying the different inversions, the final result in combination with the bass player is a set of different inversions.

The good news is, as an improviser using the chords, the fact that there are different inversions doesn’t need to affect the way you think or play. You can just think of the above as a C chord.